Following messy efforts to crack down on immigrants in Los Angeles, the Trump administration announced that Chicago would be the next target of concentrated attacks from United States Immigration and Customs Enforcement. This so-called “blitz” is already meeting resistance. In June 2025, thousands of people in Chicago took to the streets in solidarity with the resistance in Los Angeles; at the same time, demonstrators from Seattle to Chicago experimented with blocking ICE agents when they showed up to kidnap people at court appearances. Now people in the Chicago area are seeking to take strategic action at bottlenecks in ICE operations. In this report, participants in the blockades targeting an ICE facility near Chicago recount their experiences and share their preliminary conclusions.

In the early hours of September 19, people congregated outside of the ICE processing facility in Broadview, Illinois, a suburb west of Chicago. Gathering far earlier than the publicly announced mobilizations set for 7 AM and later for the evening, we hoped to catch federal agents in the act of transporting kidnappees from around the Midwest.

The processing center in Broadview holds roughly 150 prisoners at any given time; it serves as a hub for ICE activity across the Midwest. Higher-capacity ICE detention centers are illegal in Illinois, making the location a logistical chokepoint in the transportation of prisoners. As federal resources for this center have ballooned to satisfy far-right politicians’ desire for xenophobic violence, the Broadview location has become increasingly important as a critical piece of infrastructure.

When protest activity at Broadview began, small groups initially tended towards self-sacrificial, spectacular acts—typically sitting down in front of ICE vans leaving the processing center, only to be dragged away by the Broadview Police Department. As reports and footage from each action spread and faith in the effectiveness of nonviolent resistance waned, the mobilizations changed form: the primary objective of action shifted from sacrifice to resistance. ICE began brutalizing and detaining protesters at will, and attempts to block the vans failed; in response, early morning crowds traded N-95 masks for black bloc gear and opted to follow agents instead of just sitting down.

Clearly, a more proactive approach was required. The efforts of Friday, September 19 were the result.

Friday Morning

For over a decade, on Fridays at 7 am, Broadview has bussed detainees to Indiana’s Gary/Chicago International Airport—and, more recently, to other detention centers in the Midwest. The facility responded to initial televised acts of civil disobedience by moving people out earlier and earlier.

So we woke up earlier, too. On September 19, around 4:30 am, about twenty protesters gathered by the facility. Some were dressed in black bloc, some in normal street clothes. In contrast to the previous weeks’ self-sacrificial civil disobedience, most people (with the exception of an aspiring congresswoman and her press crew) decided only to stand in front of a vehicle when it was entering or leaving. This shift enabled the small crowd to move like water.

An ICE agent on his way to work hurries away from protesters during the early hours of the morning.

The first van that tried to leave Broadview was turned back as most of the crowd surrounded it and three people sat in the driveway. Energy was high, and those present followed any agent who left the gates closely, heckling the ones who pulled up to a nearby parking lot that holds marked ICE vans, unmarked cars, and agents’ personal vehicles.

Caught off guard by the early risers, the agents were frantic, some sprinting from the parking lot to the gates of Broadview. In response to the heckling, they formed groups of three or more to walk to the facility. Some put on their gear before entering. This cowardice is worthy of note.

A group of mercenaries enters the detention center.

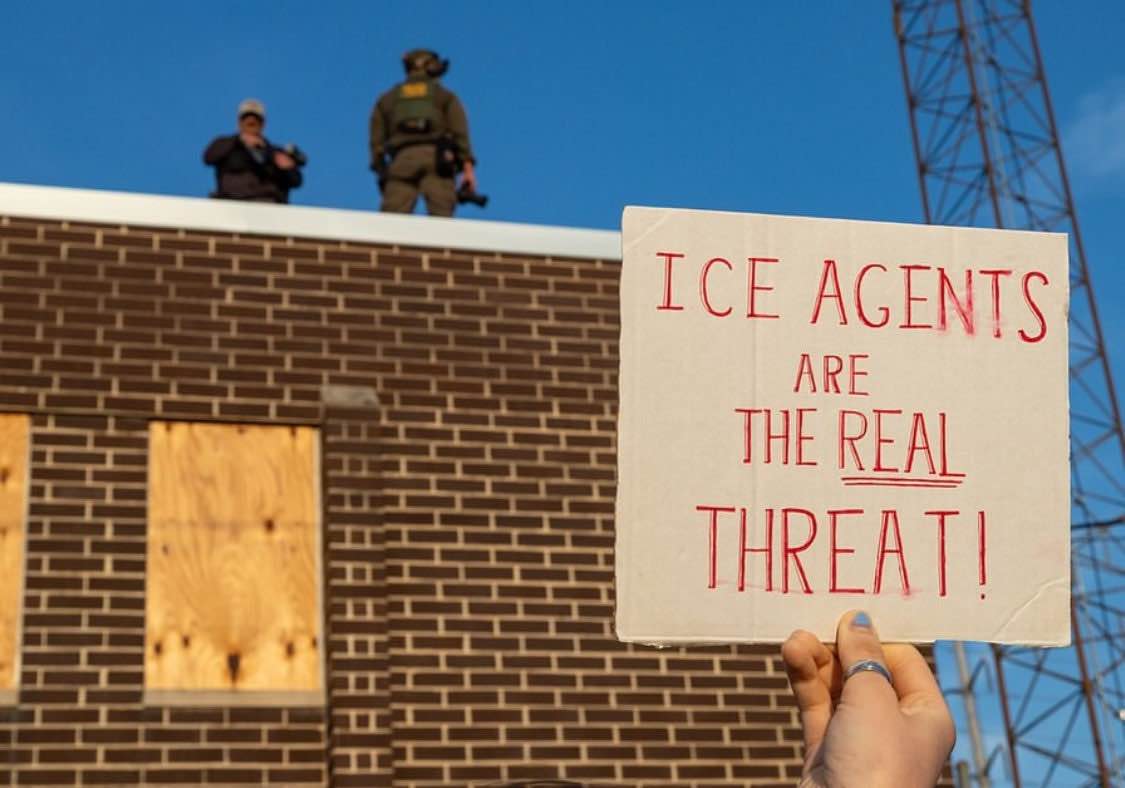

The enthusiasm of the early-morning attendees set the tone for the rest of the day. As the sun began to rise, the agents inside the facility picked up where they had left off the previous week. Decked out in tactical gear, some gathered on the roof, some behind the front gate.

Blocked by the crowd, ICE agents started driving vehicles on the curb around the protesters. There were simply not enough people, or enough technical preparation, to block or stop the cars at that time. The first arrest of the morning occurred around 6 am, when a van trying to leave the facility was once again blocked by standing and sitting protesters. This time, six special forces officers carrying pepper ball guns and a tear gas launcher rushed out of the gate. They grabbed the people on the ground and dragged them back; one woman was thrown violently against the ground, and another person was dragged across the asphalt by two agents before being grabbed and pulled through the gate into the facility.

As the agents backed up into the gate, one fired several pepper balls at people in the driveway. The pattern of special response team (SRT) agents storming out to escort an exiting or entering vehicle repeated throughout the morning.

Friday Afternoon

Between 7 am and midday, the vibes on both sides of the fence shifted. As more guards began to enter the facility with gear and buckets of munitions, distinct tendencies within the crowd became more evident. Some sections of the crowd sang, while others became more riled up after seeing protesters get repeatedly pepper-balled and dragged inside. Still others helped families attempting to reach loved ones held inside the facility.

The SRT agents tear-gassed the crowd for the first time around midday, during a standoff over exiting vans. The agents shot tear gas cannisters and pepper balls into the crowd before dragging one man back into the facility with them. Few were prepared for the chemical munitions and the crowd scattered across the street, while some helped wash eyes and move their worse-hit comrades to safety. In the afternoon, the crowd outside dwindled as people regrouped and waited for the second publicly announced demonstration.

Federal agents grab a protester at Broadview during the afternoon.

Friday Evening

A second protest had been called for 7 pm. Images of people being detained and tear-gassed had spread across the media and galvanized many who had not yet been out to Broadview.

On Friday evening, people rejoined the smaller crowd that remained from the day’s protests. Throughout the evening, two or three agents remained on the roof of the facility, intermittently shooting pepper balls at protesters on the ground. As protesters amassed around 7 pm, about thirty SRT agents gathered behind the gates. Protesters called for them to free the hundreds of people held captive inside, as well as the protesters arrested earlier that day.

Following a daytime standoff with demonstrators by the gate of the facility, Gregory Bovino, who led the ICE invasion of Los Angeles, moves in with agents and attempts to force the crowd back.

After 7 pm, shields arrived. A dozen or so militants picked them up, but the majority of the crowd stayed at a distance. Perhaps reflective of the previous week’s tendency towards symbolic acts by a small number of people, there was a significant gap between the small group of people at the front and those observing at a distance, and no organic understanding of the need for people to participate behind the front line. The people in the shield line began calling out and gesturing to the crowd, telling press to get out of the way and everyone else to pack in.

Agents stormed out of the gates around 7:30 pm. The frontliners in the shield line repelled the first wave of munitions, facing down a barrage of tear gas, pepper balls, and flash-bang grenades. But they were forced to retreat due to the combination of the agents’ “less-lethal” munitions and the disintegration of the crowd behind them. This was understandable: not everyone has protective gear, and even those of us with gas masks felt the effects of the gas. Most of the crowd was not bracing each other or the shield line.

A shield wall blocks riot munitions on the night of Friday, September 19.

The front line cannot be a specialized group that acts alone while others stand by documenting or witnessing. The specialization of relevant skills, from eye washing to jail support, leaves militants isolated when pressure ramps up. A well-organized front line integrates offensive roles with the support necessary to sustain resistance and carry out objectives.

But while the gulf between perceived “militants” at the front and folks at the back continues to impede effective defense, the growing tendency to resist points beyond it. We want to shut down Broadview, not just symbolically but completely. The strategy of spectacle is based on the notion that the repeated brutalization of our comrades will persuade those who are abducting our neighbors to stop. But as people witness these kidnappings firsthand and experience the brutality of “law enforcement,” many are gradually abandoning that approach. Some for whom the violence of the state was previously an abstract concept are turning against the mercenaries that they see standing on the roof of Broadview, looking back at them through the scope of a weapon and choosing to pull the trigger.

Crowd Control

The ICE agents themselves proved brutal but unintelligent. Several times, they appeared lost, barreling into the crowd of demonstrators before pulling back just as quickly. Despite favorable conditions, they did not know how to kettle. When agents approached demonstrators, they often broke ranks or formed a wall only one agent deep. Employing pepper ball guns, they shot sporadically and haphazardly, often without any specific target.

Agents frequently broke in the face of demonstrators, appearing shaken even by feeble chants. Likewise, the SRT typically avoided close proximity with demonstrators, despite having a more significant advantage. Whether this was due to laziness, confusion, or both, they hesitated to detain even those who actively tried to stop vehicles from leaving the facility.

This is only speculation, but it is worth remembering that the facility is relatively small, is used continuously, and holds roughly 150 prisoners at a time. In light of Operation Midway Blitz and other ICE activity in and around Chicago, it is likely that the facility is already operating at its maximum capacity. This, along with their apparent lack of crowd control experience, may have informed how agents and SRTs engaged with demonstrators.

A flash-bang grenade explodes as federal agents attack the shield wall.

Becoming Proactive

If the courage we are seeing is to escape specialized and repetitious clashes with better-equipped state forces, it will need to forgo media spectacle to take more proactive efforts against deportation infrastructure. We need to define what it would mean to achieve victory over the state’s agents and facilities and articulate the fight for liberation that underlies the shift towards more generalized confrontation with the representatives of the state and capital. Acting on that scale requires expanding beyond a specialized activist crowd (not to mention less laudable, more plainly careerist aspiring politicians) to build relationships with those who live around the facility and, more broadly, with everyone whose instinct is already to protect people from ICE.

All over the country, people have spontaneously taken clever and timely actions against raids in their neighborhoods, acting before specialized activists and NGOs arrived to urge them to limit themselves to documenting and witnessing. Rather than relying on reactive rapid response networks that rarely arrive in time, given the speed of raids, more proactive action could involve targeting chokepoints around local deportation pathways like Broadview, or, as in Los Angeles, setting up community defense centers at hotspots of federal activity. Any effective anti-ICE strategy will depend on the actions of locals who choose to intervene in their neighborhoods. Though the media has downplayed many of these stories, the clashes at Broadview are only possible because of the courage of those who have chased ICE out of their neighborhoods in Los Angeles, Chicago, and elsewhere around the country.

After the shield wall scatters, the remaining protesters move forward to meet agents at the gate.

We also need rapid tactical development. Given the Chicago Police Department’s reliance on kettling, collaborating with organizers, and, when they so choose, batons, Chicagoans are less equipped to deal with tear gas than people in Los Angeles were. This is changing quickly, but it has taken some serious learning.

We’ve seen increasing tactical openness. During the first phase of anti-ICE struggles, hard and soft barricades were used to block the loading docks of a downtown immigration court, delaying deportations there by years at a time; during the struggles at Broadview, de-arresting has become the norm, shields have become more widely accepted, the use of protective gear like respirators and goggles has become common, and protesters are beginning to return tear gas canisters to ICE agents. These developments are not necessarily connected to any particular political commitments; we still see people who are willing to hold off agents and block vehicles, yet also quixotically call the police to report ICE activity.

NGOs and Recruitment-Drive Organizations

Emerging autonomous activity to stop deportations shows the potential of stepping outside of recruitment-based organizations’ long marches to nowhere and NGOs’ emphasis on legal support after deportation arrests have already occurred. This activity has grown in large part due to the NGOs abandoning key locations and struggles.

The Illinois Coalition for Immigrant and Refugee Rights and Organized Communities Against Deportations, the two main nonprofits that dominate organizing against deportations in Chicago, did not take action against the repeated deportations at immigration court earlier in summer 2025, while autonomous groups stepped in to barricade the loading docks, coordinate phone zaps, heckle management, flyer other occupants of the building, and conduct court support for people with hearings inside. Those actions shut down the court on multiple occasions, pushing hearings back years, and ultimately forced the building management to revoke ICE’s access to their loading docks, putting a stop to kidnappings at that location. This would not have occurred had autonomous demonstrators not blocked the flow of commerce into and out of the building.

Beyond calls and petitions, the NGOs similarly abdicated actions around Broadview. That was one of the factors that enabled the actions of the preceding weeks to take place.

An umbrella serves as a makeshift defense during the clashes.

Internal Tensions

When people first mobilized against the Broadview facility a few weeks ago, it had hardly received any public attention, so some people focused on press strategy. This has caused tensions, from social media influencers issuing dispersal advice to swarms of press preventing de-arrests and isolating those who attempt to protect activists targeted for arrest. Those who have involved press and public opinion in their activity the most have ended up letting that attention hinder their approach to strategy. While it is clear that we have to consider press and public attention in our movements, we should never compromise this moment’s most promising goal: driving ICE out of everywhere.

While demonstrators have proved that they can build critical mass, they have sometimes limited their own effectiveness. In the weeks leading up to September 19, messaging around the efforts to shut down Broadview was taken up by a range of people and organizations who, presuming they knew best, used notions like “safety” and “visibility” to discipline demonstrators to their own benefit. The assumption that the only imaginable goal of these protests is to speak truth to power—rather than shutting down Broadview—left people unprepared for the confrontations that ensued. On the night of September 19, when “shut it down” meant taking serious risks, this meant that there was no second line to back up the shield wall. Without backing, the front line could not hold, and this gave the SRT units a chance to hunt down scattered demonstrators.

Nonetheless, thanks to consistent protests and media coverage, people in the neighboring areas have begun to turn out. Without funding or support from any big-name organization or coalition, the fight to shut down Broadview depends on the courage of ordinary people.

A protester’s umbrella shows the effects of pepper ball rounds.

The Shutdown Fiasco

As this piece was being composed, a series of leaks from the Department of Homeland security suggested that the Broadview processing center was being temporarily shut down. Something similar had taken place earlier at the Delaney Hall detention center in New Jersey after protesters blocked and eventually breached it, though that site had come back into operation with better security a few months later.

However, following a public meltdown featuring a DHS Assistant Secretary and eager claims of victory by organizations that had not been particularly visible on the ground, it was officially confirmed that the Broadview processing center would remain open. As of the morning of September 23, the processing center has been blocked off by tall metal fences, presumably to impede protesters’ access to its entry and exit gate, and clashes continue outside. The buses we have seen exiting the facility to drive to the Gary/Chicago International Airport were transporting detainees who had been forced to sign self-removal papers.

On the one hand, we’d been aware for some time that the processing center was at capacity. It is a relatively small building with limited bed space; this makes it a point of vulnerability for the entire deportation apparatus in Illinois and its adjoining states. On the other hand, the confusing sequence of events that ended with the center remaining open suggests internal disarray. This matches the reports we’ve heard from inside the facility itself that many of the mercenaries involved are working together for the first time, often at cross purposes.

It’s possible that at one level of the ICE and DHS bureaucracy, the decision was made to avoid a Delaney Hall-type situation and improve security, but higher-up leadership balked at the suggestion and insisted that the facility remain in use. In any case, it is clear that on some level, what we are doing is working. It is creating stressful and chaotic situations for our enemies, leading to internal conflict. The threshold of effort necessary for success may be lower than we thought, and our enemies more fearful than we anticipated. At the same time, the sluggish and inept federal bureaucracy routinely experiences internal conflicts of this sort, and we should seek to take advantage of them.

ICE out of everywhere!

The fight’s not over! Push through and break down the walls!